Ch 5: Adult Dog Training (2 years+)

As dogs mature, they develop many doggy interests that may compete with dog training. For example, dogs may find that sniffing the grass, playing with other dogs and chasing squirrels are all much more exciting than listening to their owners and following repetitive instructions — come, sit, down, heel, sit, heel, sit, etc. Puppy training techniques begin to fail, environmental stimulation causes sensory overload and many dogs become hyperactive or reactive to other dogs and people. Owners become frustrated by the dog’s hyperactivity and inattentiveness and the relationship starts to go downhill.

Unless regularly given the opportunity to explore new surroundings and meet unfamiliar people and dogs, as dogs grow older, they become less accepting of their environment. Older dogs become more wary of the world in general and especially of strange, scary and unfamiliar stimuli. Make sure you give your adult dog plenty of time to adjust to new situations and employ classical conditioning to build positive associations when introducing dogs to new experiences or people.

The very first item on the agenda is to learn to control your dog’s rambunctiousness and rumbustiousness. A very successful training ploy is to “put behavior problems on cue” — to train the dog to bounce and bark on command, as in the Jazz-up & Settle Down and the Woof/Shush exercises. Then, the problem, which worked against training, now becomes an enjoyable game — a reward to use while training. Classical conditioning has an additional calming effect by teaching the dog to form positive associations with the physical and social environment. However, the success of adult dog training depends on the magical All-or-None Reward Training techniques.

All-or-none reward training techniques are easy, simple and extremely effective. The techniques have similarities to clicker training in that no commands are given and the dogs are neither lured nor prompted. However, all-or-none reward training is much quicker than clicker training since shaping is unnecessary. Within just a few minutes, without giving a single instruction, your dog will learn to pay attention, sit stay and to walk calmly on leash. And once all-or-none reward training techniques give you back your dog’s attention, you can go back to using the lightning-fast, lure/reward training techniques that you used with your puppy.

Important

To fast-track your adult dog’s re-education, make sure that you do not waste potential training rewards by feeding your dog from a bowl. Instead, each morning, weigh out your dog’s daily ration of kibble and place it in a container. Throughout the course of the day, you may handfeed every piece of kibble as a reward for good behavior.

Jazz Up & Settle Down

Many owners experience great difficulty and frustration trying to get their adolescent dogs to settle down. Many dogs bark and bounce like crazy when the front doorbell rings. Dogs perform moon loops just because the owner says, “Walkies,” or picks up the dog’s leash. And on walks, some dogs literally explode with activity and uncontrollable enthusiasm at the mere prospect of meeting a person, another dog, a squirrel, or a leaf.

Many owners ignore their dogs when they are calm and well behaved and only attempt to control the dog’s behavior when he is really out of control. Obviously, this is a most challenging way to train. And it isn’t going to work that well. First, owners should practice settling down their dogs in easier scenarios — when the dog is less excited, or even when the dog perfectly calm and relaxed. For example, while your dog is snoozing on his bed, ask him to join you to settle down on the couch. Your dog would be only willing to obey. Then owners should settle down the dog in more distracting settings. For example, when walking your dog, ask him to settle down every 25 yards and by the end of just one walk, you’ll have a very different dog — much more attentive and biddable. Finally though, owners must “confront the beast “and learn how to teach Mr. Hyperdog to settle down quickly and willingly, anytime and anywhere. This is one of the first adolescent exercises that we teach at SIRIUS® Dog Training, because this is precisely what owners have come to learn. In many adult dog training classes, dogs are never allowed to bark and bounce or express their enthusiasm and so, owners can never learn how to settle down their dogs when they are excited. Obviously, we have to allow dogs to bark and bounce in order to practice teaching them to settle down and shush. However, rather than let the dogs be rambunctious at will, we teach the dog’s to be rambunctious on cue.

Interestingly, as soon as we instruct owners to jolly up their dogs and get them to vocalize and jump in the air, most dogs simply stand and stare and observe their owners with some considerable curiosity. This is a classic example of Murphy’s First Law of Dog Training: When trying to teach a particular behavior, usually the opposite happens. With a little encouragement though, most owners quickly learn to teach their dogs to jazz up on cue, whereupon the owners may now, at their convenience, repeatedly practice teaching their dogs to settle down on cue. The jazz-up-and-settle-down sequence is repeated until every owner can get their dog to settle down and shush within three seconds.

Once the owner has taught their dog to perform a “problem” behavior on cue, the behavior is no longer a problem that works against training, instead the activity may now be used as reward to reinforce training. For example, after a lengthy period of settle-and-shush, you may instruct your dog to bounce, circle, bark, rollover, or tug as a reward. After walking calmly on leash, you may instruct your dog to pull as a reward. (Especially useful when going uphill.)

An additional benefit of having activity problems on cue is that you may now instruct your dog to let off steam when the time is convenient. For example, I would always instruct my Malamute to stick his head out of the sunroof and howl whenever we were stuck in commuter traffic on the San Francisco Bay Bridge. In fact, once, during an especially lengthy traffic jam, a BMW driver followed suit and howled back!

Classical Conditioning

Whereas eight-week-old puppies are universally accepting of people, adolescent dogs naturally become wary of anything unfamiliar, including noises, objects, dogs, people and places. It is not uncommon for adolescent dogs to become fearful or reactive. As puppies grow older, the world becomes a scarier place. To prevent dogs from becoming wary of children, men, strangers, skateboarders, other dogs, loud noises, vacuum cleaners, nail clippers, collar grabs, etc. etc. etc., take your time when exposing your puppy, adolescent, or newly adopted adult dog to novel (unfamiliar) stimuli, settings and situations and make sure you classically condition your dog not only to tolerate, but also to thoroughly enjoy all of these potentially scary stimuli.

Simply put, classical conditioning helps your dog form positive associations with all sorts of stimuli. Let’s say your puppy has grown to be scared of men. Rather than feeding your dog in a bowl, use his entire allotment of kibble for classical conditioning. For one week, take your dog to dine downtown. Sit on a bench and offer him a piece of dinner kibble each time a man walks by. For a second week, ask male passersby, “Excuse me, would you mind hand-feeding my dog? He’s really shy of men.” In no time at all, your dog will form a positive association between men and FOOD and might muse, “Ah yes, I love men.”

The most important times to classically condition your dog are when visitors come to your house, on walks, in dog parks and especially during dog training classes.

From puppyhood onwards, have every visitor to your house offer your dog a few pieces of kibble. Even though your puppy may be Mr. Sociable right now, unless you take this precaution, he will most certainly become more standoffish, asocial, and maybe antisocial as he grows older. Please do not take your puppies golden demeanor for granted. Have every household visitor offer a food treat to your puppy/dog and then your dog will look forward to visitors. Additionally, teach each visitor how to use the treat to teach your dog to come, sit and stay.

Most people walk their dogs too quickly through the environment. There is simply too much for the dog to take in — people, other dogs, other animals, noises and smells — “Oh there’s a squirrel. I smell Trixie. Hmm! I just love the smell of her urine. Trixie! Trixie! Trixie! Son of a female dog! That motorcycle was soooooo loud! Oh, oh, oh! Cat poo! Woo hoo! Yes!!! And another squirrel. Two squirrels Oh what’s my owner saying now? Oh, S.O.A.F.D! There’s Bruno. OH he’s HUGE! And his owner looks nervous. Why’s my owner jerking my leash? Is that a discarded hamburger wrapping. There’s a cat. I know there’s a cat. Can’t see it. Can’t hear it. Can’t smell it, but I know it’s there somewhere. I can feel it. She’s looking at me. Where is she? Oh NO! Children! I hope they don’t come this way. Another squirrel. Is that the mail truck three blocks away? I hope I get back home before he come.” And so it goes on. The dog’s brain goes into sensory overload. The dog is over-stimulated and instead of paying attention to his owner he becomes hyperactive or reactive.

When walking a dog, on-leash or off-leash, stop every 25 yards, let the dog take his time to look, listen and sniff and wait until he establishes eye contact (acknowledges your presence) and accepts a couple of pieces of kibble before saying “Let’s go” and continuing the walk for another 25 yards. Every couple of hundred yards, find a comfortable place to sit and wait for your dog to settle down and get used to the new environment. Offer your dog a piece of kibble every time the environment changes, for example, each time a person passes by, and maybe two pieces of kibble for a man, a piece of freeze-dried liver for a boy, and three pieces of liver for a boy on a skateboard.

When dogs visit unfamiliar environments, offering then kibble is a great temperament test for trainers, veterinarians and owners to check that the dog is at ease. If the dog refuses kibble from the owner, he is probably anxious about the environment — so give him time to adapt. However, if the dog accepts kibble from his owner but not from his veterinarian or trainer, then the dog most probably feels ill at ease with the veterinarian or trainer and so, proceed slowly — verrrry slowly.

For an adolescent or young adult dog, dog parks and training classes can be pretty scary environments, usually with a high-voltage social scene. Always give the dog a chance to relax and get used to the environment. Before attempting to train, wait until the dog settles down and appears and ease. Periodically keep offering pieces of kibble. Once the dog feels at ease, he will take the kibble and start to pay attention. Keep offering the kibble regardless of the dog’s behavior; it doesn’t matter whether the dog is hiding and peeking, barking, growling, or snapping and lunging. Keep offering the kibble so that the dog eventually forms positive associations with the class setting, the other dogs, the trainer, and other people.

Some people are afraid that offering kibble during classical conditioning might unintentionally reinforce bad behaviors. Certainly, when training, we are always classically conditioning and operantly conditioning at the same time. If you use your voice when classically conditioning, “There’s a good boy, it’s OK,” you might unintentionally reinforce all sorts of unwanted behavior. The classical conditioning still works for us but the operant conditioning works against us and makes the problem worse. In time, the dog will begin to feel OK about the situation but will continue barking and growling, or hiding and shaking, because that’s what he’s been unintentionally trained to do. However, by using food when classically conditioning, you can only reinforce good behavior because a dog cannot bark and lunge or eyeball another dog at the same time as turning to face you to take food.

For example, let’s say we are trying to classically condition a dog that is barking and lunging at another dog. We offer food, but the dog ignores our offerings and continues barking and lunging. Eventually though, the dog barks himself out and sniffs the food, whereupon he turns away from the other dog to take the food. Taking the food does not reinforce the dog’s barking and lunging. On the contrary, the food reinforces the dog for stopping barking and lunging, for turning away from the other dog and for turning towards his owner. After a couple of dozen repetitions, the dog will begin to form positive associations with the sight of other dogs. “I love it when other dogs approach because then my owner feeds me dinner.” And as a bonus, the dog’s trained response to seeing another dog is to turn away from the dog and to sit quietly and expectantly facing his owner.

As classical conditioning proceeds, the dog is less and less inclined to react in a negative manner towards the scary stimulus. Once a dog forms positive associations with stimuli, such as a vacuum cleaner, other dogs, or people, he doesn’t want to growl or snap and lunge at them.

You simply cannot do too much classical conditioning. Remember…

Operant Conditioning Rocks! But…

Classical Conditioning Rules!

All-or-None Reward Training

All-or-none reward training is the quintessence — the sine qua non — of successful adult dog training. All-or-none reward training techniques are easy, simple and extremely effective. The techniques have similarities to clicker training in that no commands are given and the dogs are neither lured nor prompted. However, all-or-none reward training is much quicker than clicker training since shaping is unnecessary. Within just a few minutes, without giving a single instruction, your dog will learn to pay attention, not to touch forbidden food and objects, sit stay and to walk calmly on leash. And once all-or-none reward training techniques give you back your dog’s attention, you can go back to using the lightning-fast, lure/reward training techniques that you used with your puppy.

Good Behavior

Taking the good for granted and moaning and groaning about the bad is without a doubt, our biggest human foible. Rather than relishing all wonderful things about life, we tend to focus on problems. This tendency is extreme when people interact with their family, friends, colleagues, dogs and horses, and especially when people evaluate their own lives.

For years and years, dog training was almost entirely problem-based. People would offer limited supervision and instruction to their dogs and them punish them whenever they broke rules that they didn’t even know existed. Yet, if we objectively time-sample behavior, we find that even very badly behaved (uneducated) dogs (and people) are actually good most of the time. For example, observe your dog for half an hour and every two minutes or so ask the simple question, “Is he being good or bad?” You will find that he is being good well over 90% of the time. But in the normal course of the day, most of a dog’s good behaviors are ignored. Instead owners are more likely to pay attention to the dog when he barks, or when he steals, chews or runs away with inappropriate articles. So much so in fact, that many dogs quickly learn that misbehaving is the very best way to get their owners attention. Indeed, many dogs will bark, steal, chew and run away with inappropriate articles simply to get their owners to respond or at least acknowledge their existence.

Dogs are social animals and absolutely thrive on social interaction, communication and feedback regarding the appropriateness of their behaviors. Dogs need oodles and oodles of attention (and affection), so lets give it to them when they are good.

One of the most magically powerful training techniques is to ignore all unwanted and inappropriate behavior and instead, to pay attention to and reinforce good behaviors.

Observe your dog and whenever he does something you like, simply say, “Good dog” and give him a piece of kibble. For example, reward your dog whenever he sits, lies down, stops whining/barking/howling/growling (shushes), stops jumping (four on the floor), looks at you, or looks cute.

Unwanted behavior offers a wonderful dog training opportunity because now owners may reward their dog for ceasing undesirable behavior. Reinforcing the cessation of misbehavior is the training technique of choice when trying to eliminate whining, growling and running away, because punishment would only exacerbate the problem, making the dog more likely to whine, growl and run away.

Similarly, rewarding a dog for the absence of misbehavior is an extremely effective training technique. Sometimes the dog may look like he isn’t doing much. But that’s precisely the point! The dog may just stand there wagging his tail, but just think of all the annoying and worrying things he could have been doing. He could have been barking, snarling, snapping, or biting! So, let’s reward dogs for not acting fearfully or antisocially.

Or, you might decide to actively reward your dog for any sociable, friendly or appeasing behavior, such as when he approaches, wags his tail, wags his butt, sticks out his tongue, raises a paw, play bows, or rhythmically shifts his weight back and forth from front paw to front paw.

Obviously, simply ignoring unwanted behavior will not cause it to be eliminated entirely, but you will see a speedy and dramatic reduction in the frequency of undesirable behavior because the dog now allocates most of his time for good behaviors, which are successful in soliciting the owner’s attention and affection, and so there is simply no time for bad behavior. After just a couple of dozen rewards, you will find that your dog is sitting and looking up at you — a perfect sit-stay and perfect unwavering attention. And you didn’t ask for a thing. All you said was, “Thank you!”

In this section, I have sometimes used the words “good” and “bad” to describe behavior. However, it is unlikely that dogs have a solid cognitive grasp on ethics and morality, or even about the concepts of good and bad. Dogs behave (chew, bark, growl, pull on leash, run away etc.) the way they do simply because that’s the way dogs behave and that’s the way owners have trained or allowed the dogs to behave. By “good” behavior, I mean behavior that owners consider to be desirable, appropriate or acceptable and by “bad” behavior, I mean behavior that owners consider to be undesirable, inappropriate or unacceptable

Pay Attention

When puppies reach adolescence, food lures temporarily lose effectiveness. The owner and their food lures now have to compete for the dog’s attention with all the more interesting stimuli in the environment. Indeed it is a rude awakening for many owners to discover that their dogs are much more interested in sniffing another dog’s butt or chasing a squirrel than paying attention to them. Most owners resort to upping the olfactory punch (and price) of their food lures. But this seldom works for long. In fact, you may identify forlorn and exasperated owners of adolescent dogs by smell, since they have finally resorted to using dried fish as a lure.

With adolescent dogs we need to temporarily change the type of lure from food to toys. Retrieval toys and tug o’ war toys work the best. Get your dog hooked on fetch or tug and then you may use the toys as lures and rewards to teach him almost anything.

Another approach is to temporarily put food lures aside and to train your dog to pay attention by using all-or-none reward training. Once your dog is paying attention once more, food lure/reward training will work as quickly and as effectively as before.

From simply paying attention to and rewarding your dog for desired behavior as described in the previous exercise, you will find that your dog is much calmer and spends much more time sitting and watching you. This is good. But now we are going to specifically train your dog to pay attention. You may perform this exercise off-leash at home or on-leash on a walk. Rather than feeding your dog from a bowl, weigh out and use his daily allotment of kibble for this and other exercises. Once you have regained your dog’s attention, kibble rewards will be unnecessary and you may feed him how you like. With an attentive dog, your praise will be more than sufficient to further reinforce his attention.

Ignore everything your dog does until he glances at you for an instant. It doesn’t matter how long you have to wait or how short the glance. For the first couple of trials you may have to wait for several minutes but soon you will find your dog will look at you within seconds. As soon as your dog glances at you, say, “Good Dog,” reward him with a piece of kibble and then take one large step (to break his gaze) and wait for him to glance at you again. After a couple of reinforced glances, up the ante in terms of time of attention required for a reward — first one second of attention, then two seconds, three, five, eight, and so on. Count out the time of attention in “good dogs” — “Good dog one. Good dog two. Good dog three, etc.” Once your dog is paying attention for 20 or 30 seconds, you will notice that he is also in a sit-stay.

Now we are going to make it a little more challenging for your dog. After praising and rewarding your dog for looking at you, as you step away, turn your back on your dog to intentionally break his gaze. Give him plenty of time because now he has to work out that staring at your backside is not sufficient, but instead he has to come round in front of you to “find your face.” Praise your dog as soon as he looks up at you and then repeat the sequence.

After a few trials, it’s time to teach your dog to pay attention on cue. Say, “Watch me,” turn away from your dog and praise him as soon as he makes eye contact. Now you will be able to perform this attention exercise in motion by asking your dog to “Watch” while you serpentine backwards away from your dog. Alternatively, ask your dog to watch you while heeling, or during sit-, down- and stand-stays.

Sit-Stay & Walk On-Leash

This is one of my all-time favorite training exercises — simply scary in simplicity and shocking in terms of magical results. This exercise actually provides the secret information that some gawdy websites promise over and over but never actually deliver. Watch our videos and see for yourself.

You start with an over-the-top, Iditarod-level leash-puller, who hasn’t paid attention to you for months, or years, and after just ten minutes fun training, you recreate your attentive dog who walks calmly on leash, looks up at you when you slow down and automatically sit-stays when you stop.

Until such a time as your dog is trained to your satisfaction, weigh out and use your dog’s daily allotment of kibble for this and other exercises. You may perform this exercise at home (indoors or outdoors) or on a walk.

Stand still, holding the leash in one hand and kibble in the other with both hands held high up and close to the body. Ignore everything your dog does until he sits. It doesn’t matter how long it takes. Eventually, your dog will sit. Many dogs will go through an entire repertoire of behaviors that worked in the past to make you walk. The dog may lunge into the leash, bark, circle and jump-up. Just stand still and ignore your dog’s unwanted antics. Wait for your dog to sit.

The longer your dog takes to sit, the better he learns that his previous attention-getting and leash-pulling antics no longer work. When he eventually sits and receives immediate praise and a piece of kibble, he will have a Eureka-experience. “Ahhhh! So sitting is the secret to get my owner to move forwards.”

As soon as your dog sits, immediately say, "Good dog," offer a food treat, and then take one huge step, stand still and wait for your dog to sit again. Your dog will likely explode to the end of the leash, thereby illustrating the reinforcing nature of you taking just one step. Wait for your dog to sit again. Most likely he will not take as long this time. When your dog sits, praise, offer a piece of kibble, take one big step and stand still once more. Repeat this sequence until your dog moves forward calmly (because he knows you are only going to take one step) and sits promptly when you stop and stand still.

Your dog has now learned he has the power to make you stop and the power to make you go. If he tightens the leash, or bounces and barks like the proverbial banana, you stop. But if he slackens the tension on the leash and sits, you take a step. After a series of single steps and standstills without pulling, try taking two steps at a time. Then go for three steps, then five, eight, twelve, and so on. Now you will find your dog will walk attentively on a loose leash and sit automatically whenever you stop. And the only words you have said were "Good dog."

Occasionally, stand still and delay giving the kibble for longer and longer periods. Praise your dog as he remains looking up at you in a sit-stay. Count out the length of the sit-stay in “good dogs”—“Good dog one. Good dog two. Good dog three, etc.”

Now we are going to teach the dog to walk by your left side. Repeat the one-step-and-sit sequence as before but this time, when you take the one big step, rotate clockwise or counterclockwise through 90, 180, or 270 degrees and stand still and wait for your dog to sit by your left side. (If you would like to walk your dog on your right side, that’s perfectly OK. Most trainers teach dogs to walk on the left.) Once your dog sits reliably by your left side each time you stop, start to thin out the food rewards and only reward the dog for straighter sits. Gradually and progressively increase the number of steps you take with each repetition. Now your dog is heeling when you walk and automatically sitting when you stop.

Alternate heeling and walking on-leash. For most of the walk, let your dog range and sniff on a loose leash, but every 25 yards or so, have your dog sit, heel, and sit, and then walk on again. Always sit-heel-sit your dog when crossing a street: sit before crossing, heel across, and then sit on the other side of the street.

Housetraining Tip

It is a good idea to have your dog eliminate before beginning a walk. It is so much easier to clean up and dispose of feces close to home. An empty dog will not pee over neighbors’ lawns or cause you to have to complete the walk carrying a plastic baggie of dog doo. To teach your dog to eliminate promptly, leave your house, stand still, instruct your dog, “Go pee, go poop,” and wait. When your dog pees, praise and offer kibble. Increase the length and enthusiasm of praise and the number of pieces of kibble according to the length of the pee. No praise for quick pretend pees, a “good dog” and a single piece of kibble for a two-second pee, “gooood dog” and two pieces of kibble for a three-second pee, etc. When your dog poops, celebrate with songs of praise and treats and say, “Walkies!” If your dog does not poop within three minutes, go back inside and walk your dog half an hour later. With a simple “no-poop-no walk” policy, you’ll soon have the speediest defecator on the planet.

Off & Take it

A major criticism of using food in training is that the dog may become over excited, worry at the food, or even bite the hand that feeds it. However, the use of food is indispensable for classical conditioning, temperament training and behavior modification. Also using food and toy lures and rewards just makes teaching basic manners easier, quicker and just so much more fun for owners. Even so, food is used only initially to teach the dog what we want him to do. Once the dog learns the meaning of our handsignals and verbal instructions, food is no longer necessary as a lure. Also, we want to phase out food rewards and replace them with more meaningful Life Rewards (toys, games, and activities) as quickly as possible. See Food Critics

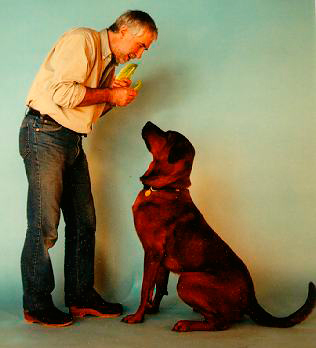

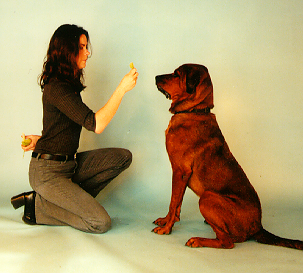

For the meantime though, we want to teach dogs to pay attention to food in our hands but never to touch, unless requested to “Take it.” The process is simple. Hold a piece of kibble in a clenched fist in front of your dog’s nose and ignore everything your dog does (licking, nibbling, or pawing your hand). Immediately praise your dog the moment he ceases contact with your hand and then say, “Take it” and open your fist so the dog may take the kibble from the palm of your hand. Repeat the sequence several times. After six to eight repetitions, you will find that your dog will quickly pull his muzzle back when you present the kibble in your fist. On subsequent trials, say, “Off,” “Don’t Touch,” or “Leave it” before presenting your fist. Count out the period of non-contact in “good dogs,” and say, “Take it” before presenting the kibble on the palm of your hand. You will also notice your dog is in a sit-stay and looking up at you with great attention.

Teaching “Off” is extremely useful for instructing your dog not to touch all sorts of things, such as, food on the coffee table, food you’re eating, food that children are eating, used-diapers, the baby, a shy dog, the cat, cat feces, or any feces or carrion. Also, by teaching “off” your dog also learns “Take it,” which will facilitate teaching your dog to retrieve and play tug o’ war according to the rules.

More Lure/Reward Training

LURE/REWARD TRAINING

The science of lure/reward training is pure and simple —as simple, in fact, as 1–2–3–4:

1. Request

2. Lure,

3. Response

4. Reward.

For example: 1. Say, “Sit,” 2. Lure the dog to sit by moving a food lure upwards in front of the dog’s nose, so that 3. As the dog raises his head to follow the food, he compensates by lowering his rump to the ground and sits — the desired Response and so, 4. Reward the dog with a scratch behind his ear, by throwing Tennis Tug ball to retrieve, or simply just give him the food.

Anyone may master the science of lure/reward training within seconds. However, it can take a lifetime to master the art. The art of lure/reward training comprises creating and compiling an exhaustive repertoire of innovative techniques to lure an animal to quickly and voluntarily perform the desired response, so that the animal may be requested to do so beforehand and immediately rewarded for doing so afterwards.

Lure/reward training may be used to quickly and easily teach your dog:

Body position changes — sit, down (sphinx, bang, side, settle), stand, rollover, beg, bow, bang, etc.,

Stays — sit-stay, down-stay (both prone and supine) and stand-stay,

Actions — heeling, jumping, backing up, walking backwards, walking on hind legs, doggy dancing and woofing and shushing on cue

Position Changes & Stays

Once you have used all-or-none reward training techniques to teach your dog to sit- and down-stay, to pay attention, to walk on leash and not to touch, you will find that your dog is now so much calmer and that you have regained his attention. Now it is again possible to use the lure/reward training techniques that worked so well in puppyhood.

Lure/Reward training is the fastest pet dog training technique to teach your dog the meaning of the instructions you use. There is no need to spend time shaping behavior. The dog is lured to perform the desired behavior on the very first trial. Consequently, the dog may also start forming an association between the command and the relevant desired behavior from the very first trial. Lure/Reward training position changes has been described in some detail in the Puppy Training chapter, Lure/Reward Training and so please go back and review that section.

The science of lure/reward training is simple and comprises a four-step process:

1. Request, 2. Lure, 3. Response, 4. Reward

When this sequence is repeated a number of times, the reward will reinforce the desired behavior which will increase in frequency and also, the reward will reinforce the associations between the Request and the Lure-movement (handsignal) and between the Lure and the relevant Response. Your dog will quickly learn to respond correctly to your handsignals, because dogs commonly communicate by body language. However, it will take a long time for your dog to learn to respond reliably to verbal commands.

The art of lure/reward training focuses on discovering the best way to immediately lure the dog to voluntarily perform the desired behavior. Food makes the best lure for initial training (at home and in puppy class) but toy lures are better for adolescent and adult dogs. Use chewtoys, squeakies, tennis balls, Frisbees, and tug o’ war toys to play-train your dog.

Once your dog is focused on the lure, he will follow any lure-movement with his nose, eyes, and ears. If he moves his nose, his head will move. If he moves his head and neck , his whole body will move. So to lure a dog to sit, move the lure upwards over his head. To get a dog to lie down, lower the lure to the ground between his front paws. To lure a dog to stand, move the lure away from his muzzle.

A cardinal rule in dog training is to always work with a minimum of three commands, so that the dog cannot anticipate the next command (as often happens when training for obedience competition). For example, if you always teach sit-stay before a recall, soon the words “Sit-Stay” will come to mean “ready… steady… GO!” and the stay will break down. On the other hand if you work with “Sit,” “Down” and “Come Here” at the same time, the dog can never predict the next command but has to wait for you to say it and so, learns to pay greater attention. If he is in a sit, he doesn’t know whether the next command will be “Down” or “Come Here.”

Anticipation is very dangerous. You do not want your dog to rush off when you say “Good Dog” but he will do if you have always said, “Go Play” immediately after praising your dog “Good Dog.” Because he now thinks that “Good Dog” means “Go Play.”

When teaching position changes, always work with three positions at the same time, for example sit, down and stand. Ask the dog to move from one body position to another. Randomize the order of the body positions. You will soon realize, that you are not simply teaching yourdog three body positions, but rather you are teaching six different body positions changes. For example, you are teaching your dog to both sit from stand (very easy) but also to sit up from the down (harder). Also, you are teaching your dog to lie down from the sit (easy) and lie down from the stand (much harder). And of course, very few people teach their dogs to stand, which means that the sit and down will be sloppy and unreliable too, because the owner is only yo-yoing the dog between two body positions. And so the dog learns, “If I am sitting, then whatever they say, I’ll lie down.” And so the dog never learns that he must listen to whatever you say.

Japan offers a wonderful exception. Dogs in Japan have the very best stand-stays because after returning home from a walk their owners instruct their dogs to stand for several minutes while they clean their dogs paws before allowing them to go inside.

To test that your dog comprehends verbal instructions for all six body position changes, take one step back from your dog and ask him to come and…

“Sit-Down-Sit-Stand-Down-Stand.”

Go for a walk and every 25 yards ask your dog to perform the S-D-S-St-D-St sequence. After just one walk, he will become extremely reliable. Reliability is important. If your dog follows your instructions, you will not become frustrated or angry and your dog will not be reprimanded or punished.

Once your dog performs random position changes quickly and reliably, praise him for longer and longer (count out the time in “good dogs”) in each position before offering him a food reward. Now, you may be able to practice random length stays in each body position. Keep track of your dog’s record length stays in each position so that you can try to beat your personal best during the next training session.

Now it’s time to teach your dog other body position changes, such as, Down on-Side, Supine-Down, Beg, Bow, Creep, Roll Over etc.

Distance Position Changes

Even though you think your dog sits fairly reliably, he probably will not sit if he is at a distance. In fact he probably will not sit if there is any variation in the training scenario. If you turn your back on him and ask him to sit, he probably won’t. If you lie on your back and ask him to sit, he probably won’t. If you ask him to sit in heel position as you continue walking, he probably won’t. But don’t worry, your dog is not being disobedient. Rather, like all dogs, he is an extremely fine discriminator and has only learned precisely what you have taught him — to sit if he is right in front of you, or if he is by your side in heel position. So, you need to teach him to sit in every possible situation and especially, if he is at a distance and distracted.

The dog’s failure to comprehend is difficult for owners to understand at first but teaching dogs is very different from teaching people. A person will generalize from one training scenario to all others, whereas a dog only learns exactly what you teach him. To teach a dog to sit in every possible situation, he needs to be trained to sit in every possible situation.

Before you can teach distance commands, you must make sure that your dog’s verbal comprehension is at least 90% reliable when he is right next to you. Why? Well, if your dog does not sit promptly and reliably when verbally instructed to do so when standing right in front of you and staring at your face, what makes you think he would sit when forty yards away and chasing a squirrel or charging another dog. When your dog is running away from you, or even when his head his turned, he cannot see your handsignals or body language (which are really easy for him to understand) and so, verbal commands are the only way to get him to respond. So, first you must check that your dog understands verbal commands when he is close to you before expecting him to respond to verbal commands at a distance.

And why should we bother teaching distance commands? Well, because when an owner has reliable distance control over their dog, the dog may now enjoy a quantum leap in terms of quality of life. The dog need no longer be confined when family and friends visit the house and the dog may be allowed off-leash in dog parks and on walks in safe areas, because the owner is secure in the knowledge, that the dog will sit when requested to do so. And let’s think about it; sitting promptly when requested will prevent or resolve pretty much every behavior problems there is. A dog cannot jump up, chase cats, chase his tail, or run off if he is sitting. (See Sit List) This is why teaching your dog an emergency distance command is so important.

So first, let’s check how well your dog understands proximal verbal commands. Go for a short walk and every 10 yards verbally instruct your dog to perform a S-D-S-St-D-St sequence until you have completed 20 sequences. Use verbal commands only; no handsignals or unintentional body language. Keep track of how many verbal commands are required before your dog responds with the correct body position change. Maybe have somebody film this exercise so that you may accurately score your dog’s performance afterwards. Then for each position change, e.g., Down from Stand, divide the number of position changes (20) by the number of verbal “Down” commands that you gave, multiply the number by 100 and this gives you the percentage reliability for this verbal command. For example if you said “Down” 43 times to get your dog to lie down on the 20 attempts, then your percentage reliability is 20/43 x 100 = 47%. Not good enough yet, so keep practicing. Once your dog’s reliability exceeds 90%, we can easily teach him distance commands.

Once your dog has a good comprehension of proximal commands, we can now teach distance commands. When teaching new and additional commands, the sequence is always the same — we follow the new (unknown) command (the one we are trying to teach) by the old (known) command, which serves as a verbal lure to prompt the desired response. In this instance, first we ask the dog to sit from a distance and then immediately afterwards we ask the dog to sit from close up. Because the two commands always occur in the same order, the dog learns to anticipate, or predict, the known proximal command every time he hears the unknown distal command. So, after a few trials he begins to respond as soon as he hears the distal command.

Ask your dog to “Down-Stay,” take one step back and then say, “Sit.” If he sits, praise him profusely and offer a couple of treats. If he does not sit within a second, quickly step back to stand toe-to-toe in front of your dog and say, “Sit.” This time he will probably respond. Praise and offer a piece of kibble. Now take a step back with him in a sit-stay and this time instruct him, “Down.” Praise and reward him profusely if he responds correctly and if not, simply step back and ask him to lie down again.

Please remember, he is not being dumb or disobedient, he just doesn’t understand distance commands yet. But after just six to eight pairings of the distance command followed by the proximal command, he will soon start to respond as soon as he hears the distance command. Now training speeds up and you will find he quickly learns to sit when you give the instruction from two yards away, then three yards, then five, ten, twenty, and so on.

To get your dog used to working in different environments, first practice with your dog off-leash indoors, in your yard and in friends’ yards. When on walks, practice asking your dog to sit when he is at the end of his leash. Then practice with your dog on a long line, or Flexi Leash. Now, you are ready to practice with your dog off-leash in dog parks and other safe areas.

Stay Proofing

When you have a lightning-quick emergency Sit plus a rock-solid unbreakable Sit-Stay, you have a pretty well-trained dog that will have a better quality of life because people will welcome his integration into the social scene.

Proofing stays comprises increasing duration, distance, and distractions. Start by teaching short stays simply by delaying the food reward after a position change and counting out time in “good dogs” — “good dog one, good dog two, good dog three etc.” Alternate periods of instructive feedback — "Good Sit-Stay Rover" — with short periods of silent appreciation. With each successive trial, gradually decrease the amount of praise and increase the length of silence.

Most dogs will give you lots of warning that they are about to break the stay; first they look away, then they sniff away, and then they go away. So, if your dog looks away from you, or if he even looks like he is about to break a sit-stay, for example, simply re-instruct your dog, “Rover, Sit!” No need to shout, but do create a sense of urgency and quickly get your dog sitting again. Even though he has moved out of body position, do not give him time to move from the spot. Get him back sitting as quickly as possible and praise him as soon as he sits again. Only use your voice as an instructive reprimand. Never use your hands to re-position your dog, otherwise it will be a longtime before you have any distance control over your dog.

Always train with a stopwatch, so you have a good objective grasp of your dog’s reliability. Remember, to practice at least three types of stay — sit-stay, down-stay and stand-stay. Do not forget stand-stays. You will find that the more you practice stand-stays, the more rock-solid your dog’s sit- and down-stays. Practice standing toe-to-toe in front of your dog, until your dog comfortably performs a 30 second stand-stay, a one-minute sit-stay and a three-minute sown-stay.

Now it’s time to gradually and progressively increase distance. Take one step back and after just one second return to your dog and praise him. After every successful short proofing episode, always return to the toe-to-toe position and praise your dog to “capture” the stay. Then take two steps back and after two seconds return to your dog and praise. Then take three steps back and after three seconds return to your dog and praise. With each successive trial, gradually increase the distance. Should your dog look like he is about to break, immediately re-instruct him to “Sit.” This is why we taught distance position changes before teaching stays. Unless you have an arm like Inspector Gadget, verbal commands are the only way to immediately correct and reposition your dog at a distance.

Now it’s time to gradually and progressively increase distractions. Of course by increasing the distance and distractions in this fashion, the cumulative duration will increase dramatically. First we to get the dog used to silly and unexpected things that we do. Most dogs will break a stay if the owner simply gets down on the ground and rolls over. This is not good enough. We want the dog to reliably stay when around children and children spend a lot of time jumping, skipping, shouting and rolling on the floor. So, let’s gradually proof the dog to stay when we move slowly, quickly, when we jump, clap our hands, laugh, sing, and perform all sorts of silly walks and actions. Remember, after each incremental proofing episode, return to your dog and praise. After thirty minutes or so, your dog should be able to remain in a sit-stay while you kneel down, approach your dog on all fours, kiss him on his nose, rollover, waggle your arms and legs in the air, squeak, and then stand up to return to your dog and praise.

Now comes the fun part, you are going to praise your dog for staying, while other people try to get your dog to break. Check out Musical Chairs competition in the K9 GAMES.

Heel On-Leash

Teaching your dog to heel has been described in some detail in the Puppy Training chapter, Lure/Reward Training and so please go back and review that section. Here, we shall present some additional tips.

Use food or toys in your left hand to lure your dog to heel on your left side. Each time before stopping, use your right arm (across the front of your body) to signal your dog to sit by your left side.

Practice short sit-heel-sit sequences in a straight line, then practice turns in place — sit-turn-sit and eventually, turns in motion. Slow down your dog (move your left hand lure backwards) before turning left but speed up your dog (move your left hand lure forward) before turning right.

It is really important to teach your dog to slow down (Steady) and to speed up (Hustle) on command. Forging ahead and lagging behind are the two major problems when heeling and of course, each is the antidote for the other. By teaching your dog to slow down and speed up on command you can prevent a lot of tight-leash walking and leash-jerks.

To teach your dog to slow down. Walk at a fast or normal pace and 1. Say, “Steady” 2. Immediately and dramatically reduce your speed so that 3. Your dog slows down to accommodate to your change in pace, and 4. Praise your dog. After half a dozen or so repetitions, your dog will anticipate that you are about to slow down whenever he hears you say, “Steady” and so, your dog learns that Steady means slow down.

To teach your dog to speed up: Walk at a slow or normal pace and 1. Say, “Hustle” 2. Immediately and dramatically increase your speed so that 3. Your dog speeds up to accommodate, and 4. Praise your dog. After half a dozen or so repetitions, your dog will anticipate that you are about to speed up whenever he hears you say, “Hustle” and so, your dog learns that Hustle means speed up.

Practice by frequently and randomly changing gears between fast, normal and slow when walking your dog in a straight line on sidewalks. Once you have taught your dog Hustle and Steady, walking your dog on leash will be so much more enjoyable for you, and for your dog. Also, Hustle is the solution to slow recalls. Shouting at your dog will usually make him slow down. I mean, who wants to hurry to a person who’s shouting at them. But if you say, “Hustle” at least your dog now knows that you would like him to speed up.

Woof/Shush

So many owners, or to be more precise, their neighbors, find excessive barking to be an intolerable problem when dogs are left at home alone. But also, many owners find excessive and uncontrollable barking to be a problem even when they are at home with their dogs. The solution is simple. Teach the dog to shush on cue. This may sound OK in theory but many owners experience huge problems trying to put theory into practice, largely because they try to teach the dog to shush when he is amped up and barking so loud that he cannot even hear the owner’s instructions. We have a better way.

First, let’s put the “problem” on cue and teach the dog to speak on command. Some may think this strange: “My dog barks so much, so why on earth would I teach him to bark more?” Well, if you have taught your dog to speak on command, you may now teach your dog to shush at times when your dog is not over-the-top with excitement and at times that are convenient to you.

Lure/Reward training always comprises the same four-step process:

1. Request 2. Lure 3. Response 4. Reward.

And so to teach your dog to speak on cue:

1. Say “Speak” 2. Lure your dog to speak, and 3. When the dog speaks, 4. Reward your dog. However, what shall se use for a lure? How about having an accomplice ring the doorbell? After six to eight repetitions of the training sequence, your dog will learn that “Speak” predicts that the door bell is about to ring and so, he will bark when you say “Speak” in anticipation of the doorbell.

Lure/Reward training is so quick and easy, we may as well teach the dog to shush at the same time. But again, what shall we use as a lure to shush the dog? Certainly, a food treat is the very best lure. A dog cannot sniff a food treat and bark at the same time. These are two mutually exclusive behaviors. Go on, try it yourself.

And so, the Woof/Shush training sequence becomes:

1. Say, “Speak”

2. Accomplice rings the doorbell or knocks on the front door

3. Dog barks at the doorbell

4. Praise your dog for barking, “Good boy! Good woofs!”

1. Say, “Shush!”

2. Waggle a piece of freeze-dried liver in front of your dog’s nose

3. Dog sniffs food and stops barking

4. Praise your dog, “Good Shush. GoooooodShush.” And then give your dog the treat.

Repeat the above woof/shush sequence a number of times and with each repetition, progressive increase the length of shush-time following each barking session by delaying giving the food treat. You may count out the length of the shush-time — “Good shush one. Gooood shush two. Goooood shush three… etc.”

Now practice on a walk, so that your dog learns to Speak and Shush in a variety of different settings.

Adopting an Adult Dog

Adopting an adult dog can be a marvelous alternative to raising and training a puppy. Alternatively, a new adult dog can be a full-time project. Adult dogs can be perfect or problematic — carrying the behavioral benefits or baggage of their previous owners.

Take your time to search for the right dog for you and only choose one that you know your family knows how to train. Some shelter and rescue dogs are purebred, but most are one-of-a-kind mixed-breeds.

Some shelter dogs are well trained, well behaved, friendly, and simply in need of a caring human companion. Others may have a few behavior problems (housesoiling, chewing, barking, hyperactivity, etc.,) and require their puppy education in adulthood. Other dogs are shy and fearful and require a dedicated owner who is going to spend the time that it takes to rebuild the dog's confidence.

Raising and training a puppy requires a lot of time and know-how. The puppy's behavior is always changing, for better or for worse, depending on his socialization and training. However, an adult dog's behavior and temperament are already well established, for better or for worse. Traits and habits may change over time, but compared with the behavioral plasticity of young puppies, an older dog's habits are much more resistant to change. Whereas temperament problems may take longer to resolve in an adult dog, good habits are also just as hard to break. Thus the key to adopting a good shelter or rescue dog depends on selection, selection, selection! Take your time to test drive plenty of prospective candidates. The perfect dog is waiting for you somewhere. Be patient, search well, and be realistic about your choice, i.e., choose with your brain as well as your heart. When selecting an adult dog, you need to evaluate whether you like the dog, whether the dog likes you (and other people), and the dog's basic manners and household etiquette.

Mutual Affection

All family members must be involved in the selection process and agree 100% on the final choice. You must equally check that the dog likes all family members. Make sure that the dog eagerly approaches each family member and thoroughly enjoys being handled and stroked. Additionally, check that the dog likes other people. Observe the dog's behavior when he interacts with a wide variety of people, especially children, men, and strangers. The most important quality in a companion dog is friendliness: he should enjoy the company and attentions of people. If he is at all fearful or standoffish, you will need to devote time to teach him that people are non-threatening.

Test-Driving

Make sure that you get a good feel for your prospective dog before you take her home. First, check her general demeanor. Is her kennel soiled or clean? Does she play with chewtoys? Is she calm and quiet, or hyperactive and barking? Make sure all family members spend plenty of time "test-driving" the dog. Check to see that everyone can get the dog to pay attention, come when called, sit, lie down, and roll over. Take the dog for a spin around the block to evaluate how she walks on leash. Especially spend lots of time handling and petting (examining) and hugging (restraining) the dog. Check that she enjoys having her muzzle, ears, neck (and collar), paws, and rear end handled. If you find she has areas that are sensitive to touch, check to see how she responds to progressive desensitization exercises. There is little point in sharing your home with a dog that you (or others) cannot touch.

Your Dog's First Couple of Weeks at Home

An environmental change offers a wonderful opportunity for a dog to learn new household rules. First impressions are extremely important and leave an indelible impression. Regardless of your new dog's presumed housetraining and chewtoy-training status, teach her where to eliminate, what to chew, and how to settle down calmly and quietly during her first couple of weeks at home. In the beginning, your dog is likely to be somewhat stressed with all the recent changes in her life. She may be depressed, or she may react with exuberance (hyperactivity and barking) in her newfound home. She may become anxious (bark, chew, pee, and poop) when left alone.

It is incredibly important that your dog does not establish any bad habits during her first couple of weeks at home. Consider a short-term and long-term confinement program (see Puppy’s First Month: Home Alone), so that housetraining and chewtoy-training are errorless. For the time being, do not feed your dog from a food bowl. Instead, have family, friends and strangers handfeed most kibble as training lures and rewards for housetraining, classical conditioning, and teaching basic manners. Stuff the rest of her kibble into Kongs to teach her to settle down quietly, calmly, and confidently. Once your dog adapts to her new surroundings and human companions, she has a lifetime to enjoy full run of her new home.

Fearful Dogs

Many dogs are undersocialized and may become fearful in the shelter environment. You are a saint to rescue a fearful dog from the stress of a shelter environment, but you must realize that for fearful dogs, confidence-building can be an extremely lengthy and heart-rending procedure. You must have both the time and the know-how. The last two dogs that I adopted were fearful and aggressive toward men and strangers. Both dogs became friendly and confident but each one required a couple of years work to help them reach that goal. (For information on how to rehabilitate a fearful dog read Help For Your Fearful Dog by Nicole Wilde.) To learn more about training, read the Open Paw Four-Level Training Manual and Doctor Dunbar's Good Little Dog Book. To locate adolescent and adult dog training classes in your area, contact the Association of Pet Dog Trainers

A good place to search for the right dog for you is the Dogtime matchup.